Give before midnight on July 31 to double your impact where trees need us most. CHOOSE A PROJECT

Private Lands: The Next Reforestation Boom?

Huge parts of the American Southeast are privately owned. That’s good news for reforestation efforts.

January 31, 2024

Ask a biologist why trees love growing in the American Southeast, and you might be surprised at the answer.

“We are a disturbance-based ecosystem,” says Lisa Lord, Conservation Programs Director at the Longleaf Alliance. “Whether it’s wind events, hurricanes, fire...all of that disturbance and unique coastal influences create little microclimates” that trees love.

But for centuries, the American Southeast has been facing other disturbances, too — not from Mother Nature, but people. Early settlers clear-cut forests to build houses, ships, and railroad tracks. They also suppressed the low-intensity fire that forests crave for fresh nutrients.

Considering the severity of the damage, American Southeast forests have made a triumphant comeback. This time, humanity is to thank. Specifically, family forest owners working to keep their trees thriving for future generations. But the disturbances they face today — extreme weather, urbanization, financial strain — are putting Southeast forests in jeopardy.

Of the 39,320,000 acres of land suitable for reforestation in the American Southeast, an estimated 85% is privately owned. Prioritizing it for tree-planting efforts is essential to maintaining a region the US Forest Service has called “part of a strategy to slow global warming.”

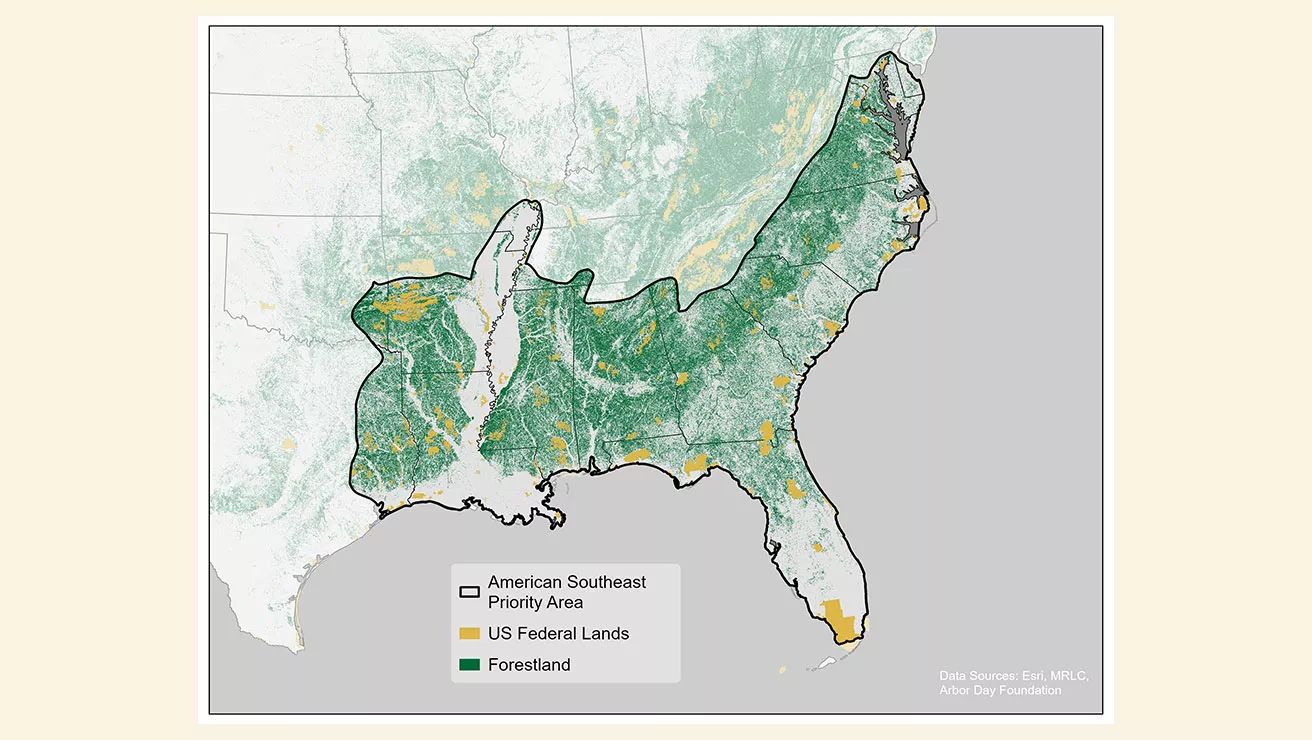

Federal Land and Forest Land—Only small portions of the American Southeast are owned by the federal government. Most of it is in private ownership.

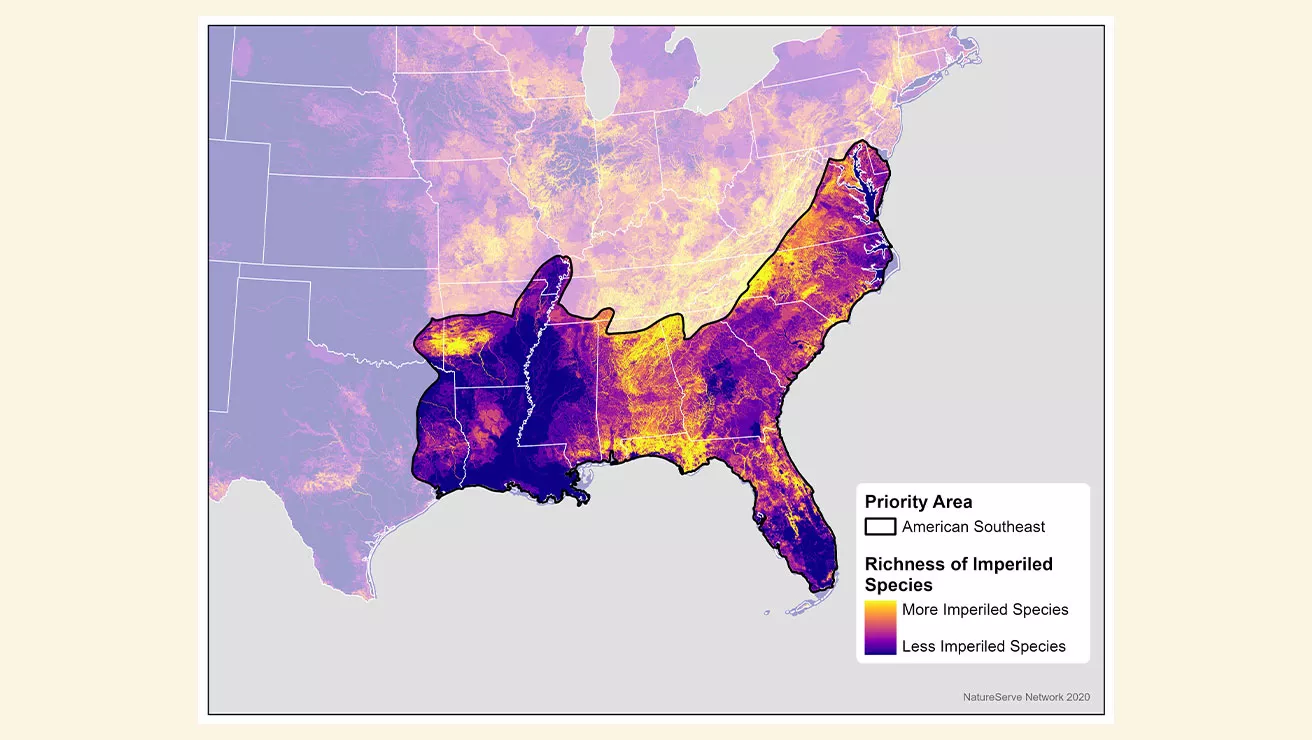

Imperiled Species—The American Southeast is home to a high number of imperiled species that rely on healthy forests.

An essential ecosystem

Forests are iconic to the American Southeast, ecologically and culturally. The trees naturally capture carbon, mitigating the effects of climate change. They provide rich habitat for keystone and at-risk species, like an endangered tortoise whose population returned in recent years, thanks to conservation efforts.

The forests of the American Southeast are also important for the region’s water supply. In the Southeast, forests filter the water supplied to 14 million people. Without healthy forests, water filtration costs rise, aquifers aren’t recharged as easily, and flooding damage can run rampant. A healthy water supply requires healthy forests.

Historically, forests have also been a reliable source of income for families in the area. Sustainable forest management requires regular thinning (think strategic tree removal) to prevent insect infestation and disease and reduce extreme fire risk. Landowners can then sell the timber for products like flooring and furniture.

In short, the forests of the American Southeast are essential for ecosystem health and community well-being.

Mounting threats to historic forests

Southeast family forests often go back generations. But as today’s landowners consider what’s next, they face a choice: preserve their forest for family to inherit, or accept one of the endless lucrative offers to convert it for agriculture or urbanization. It can be a gut-wrenching decision.

48% of family forestland is owned by people 65 years or older

For one, preserving a forest is expensive. It often involves hiring an outside consultant to perform maintenance crucial to forest survival. Tasks like reducing fire risk, controlling invasive species and pests, managing the thinning process, and planting new trees must be done right. If not, forestland will become totally uncontrollable, and more likely to be lost to urbanization or agriculture. In other words, useless to wildlife and offering zero potential for carbon removal.

Cost of reforesting after a hurricane

The costs of reforestation after a hurricane are prohibitive for many private landowners.

And while planting trees can help combat climate change, its effects are already taking out forests. To keep an area forested, you need quality seedlings for new growth, which aren’t cheap. To afford them, landowners count at least partially on timber revenue from thinning. But with climate change making hurricanes more intense and longer lasting, a single storm can wipe out 15 years of income in one day. Reforesting after a hurricane is costly — up to $1,000 per acre to clean up and another $300 per acre to replant.

In 2018, Hurricane Michael hit the panhandle of Florida, destroying three million acres of forest, and causing more than $1 billion in timber losses. Will Leonard, a forestry consultant with Timberland Solutions in Florida, remembers the cost being too great for his clients to pay out-of-pocket.

“In a normal situation, landowners would take part of the proceeds from harvest and use those proceeds to cover their reforestation costs. A disaster scenario like this, even if a producer was fortunate enough to salvage their timber, they receive pennies on the dollar for it.”

Grants, like those administered by the Arbor Day Foundation, help bridge the gap between what landowners can contribute and what’s needed for forest recovery.

Inheritance can be sticky, too. If you’re new to the land, hiring a forester, making a sustainable forestry plan, and conducting low-intensity burns can be pretty intimidating.

“We’re increasingly seeing younger landowners — who may not have stepped foot on the land their entire lives — inheriting lands from their parents, and they don't know what to do,” says Carol Denhof, President at the Longleaf Alliance. The Alliance formed in 1995 with the express purpose of connecting private landowners to resources to maintain their forest.

If that new landowner decides they’re in over their head, they may decide to sell, and the forest will likely be lost.

In some cases, multiple siblings inherit the land. Two may decide to sell while another decides to keep it in the family. It creates a patchwork of forestland and non-forestland that disrupts ecosystems (wildlife doesn't care about property lines).

When land is converted from forest to a housing development or agricultural field, it loses its carbon sequestration potential, animals lose their habitats, and a regional culture of forestry is erased even further.

Species in American Southeast forests

- Black Spotted Newt

- Houston Toad

- Gopher Frog

- Florida Bonneted Bat

- Red-cockaded Woodpecker

Alone, landowners may face a lack of resources and confusion about where to turn — for financial assistance, education, advice, and camaraderie. But together, they represent the forest’s best hope for restoration.

Arbor Day Foundation partners like the Timberland Solutions, Longleaf Alliance, Partnership of Gulf Coast Land Conservation, and the Georgia Forestry Commission are connecting landowners to the educational and funding resources they need — and connecting them to each other. As a result, they’re helping to strengthen the pride of owning forestland and the confidence to keep it thriving.

How the Arbor Day Foundation is helping

Mother Nature doesn’t know the difference between private and public land, so the Foundation works on both. We take an “all of the above” approach to building a network for reforesting the Southeast. By forming relationships with landowner groups, as well as professional consultants in the area, more landowners get access to essential funding they need to restore their lands.

And by providing financial support, the Foundation is making it easier for landowners to stay in the game, whatever challenges lie ahead.

A prime region for impact

Despite the challenges to landowners, the Southeast remains an incredible region to grow trees. The climate and natural weather patterns create an ideal environment for tremendous growth, according to Leonard. Add to that a motivated audience of family landowners working to keep forestland, forestland, and it’s an area with incredible potential for impact.

“There’s more opportunity to move the needle in the Southeast with reforestation projects than anywhere else,” Leonard says.

The American Southeast in Focus

We plant trees around the world, but focus our efforts on key regions where trees can do the most good. In the American Southeast, we’re supporting efforts to restore longleaf pine and other native species at a massive scale. Since most of the land is privately owned, the Arbor Day Foundation is working with landowners and public entities alike to further reforestation efforts.