Give before midnight on July 31 to double your impact where trees need us most. LEARN MORE

Guest Post by David Taylor, Johns Hopkins University

The Arbor Day Foundation’s ambitious tree-planting initiative to plant 100 million trees has deep roots, so to speak. They include a World War II campaign to plant trees across America. Every Arbor Day from 1942 through 1946, a patriotic tree-planting drive brought thousands of children, adults and politicians together to increase the country’s tree cover.

Mostly, they were planting cork oak seedlings. There was a reason for that.

Tree Products in American Life

The planting campaign was the brainchild of the head of a Baltimore-based bottle-cap company named Crown Cork and Seal. A fact of life from then rarely remembered today: thin slivers of cork were used in bottle caps to make the seal tight and keep the pop in carbonated sodas.

In fact, before we had cheap plastic, thin sheets of cork (the bark from the cork oak) were used in all kinds of seals and insulation. America imported nearly half the world’s cork output every year for these uses.

All that cork came from Mediterranean forests in Europe and North Africa. In 1939, those imports were threatened when Nazi Germany imposed a blockade of Atlantic shipping. Hitler ordered U-Boat submarines to sink merchant ships that defied the blockade.

If you led an American company that relied on cork trees abroad for your business, you might consider growing American self-reliance with millions of cork oaks on American soil. That’s what Charles McManus Sr., the head of Crown Cork and Seal, decided to do.

Trees and Security

McManus grew concerned in October 1941 when the U.S. Commerce Department published a report about the rise in cork use, from bottle stoppers to all kinds of defense insulation. The report said that the American cork industry affected so many other sectors that it had become a matter of national security. America needed cork.

That’s when the idea of the McManus Cork Project started. McManus’s staff found cork oaks growing in California and wondered how they got there. The company worked with a forester in Berkeley named Woody Metcalf, who was devoted to California’s plant life. In decades of hiking around California, he had found dozens of big cork oak trees. Metcalf’s research showed that the state’s Quercus suber plantings followed an 1858 shipment of acorns from the Mediterranean, arranged by the U.S. Patent Office in San Francisco. With support from Crown Cork and Seal, Metcalf surveyed all of the West Coast cork oak trees south to Los Angeles.

Metcalf and his team then practiced the harvest of cork on a few trees, stripping the cork on the larger trees with the tools and care that Portuguese cork growers used. Why doesn’t stripping the cork kill the tree? Cork oak is the only tree species that grows an annual ring in the outer bark as well as in the wood, so the tree can survive having the bark peeled back. The cork can be harvested every eight to 10 years and the tree can live for over 100 years.

Metcalf sent samples from the larger California trees to the Crown Cork lab in Baltimore. When the tests confirmed their cork was of very good quality, those trees became the focus of an acorn gathering effort.

Acorns Are for Growing

By 1945, the McManus Cork Project had gathered and distributed millions of acorns, both from the California trees and from special collections in the oak’s native range.

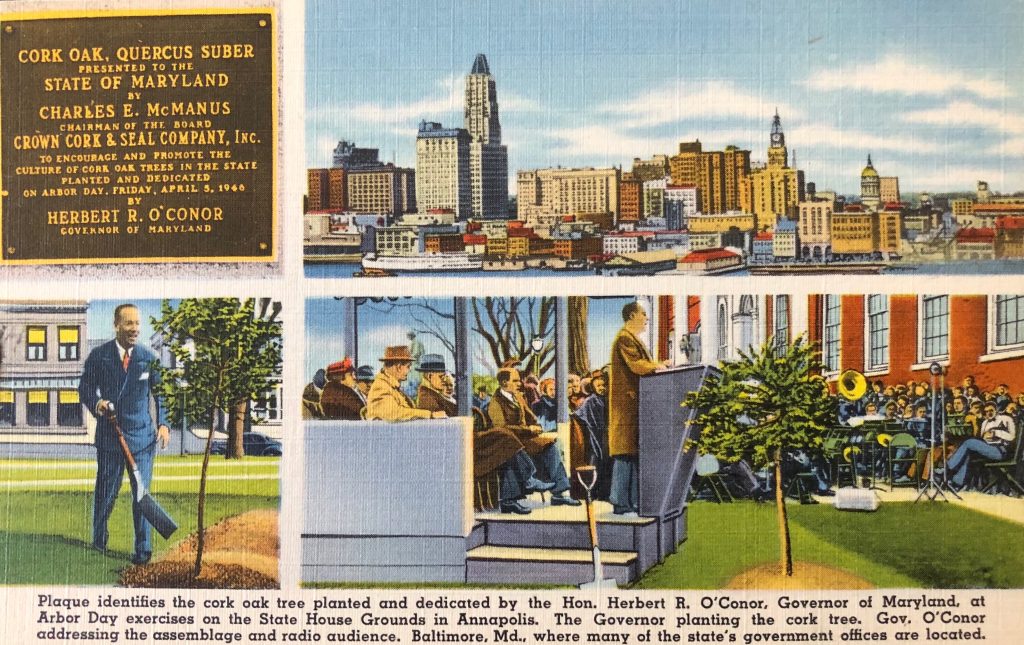

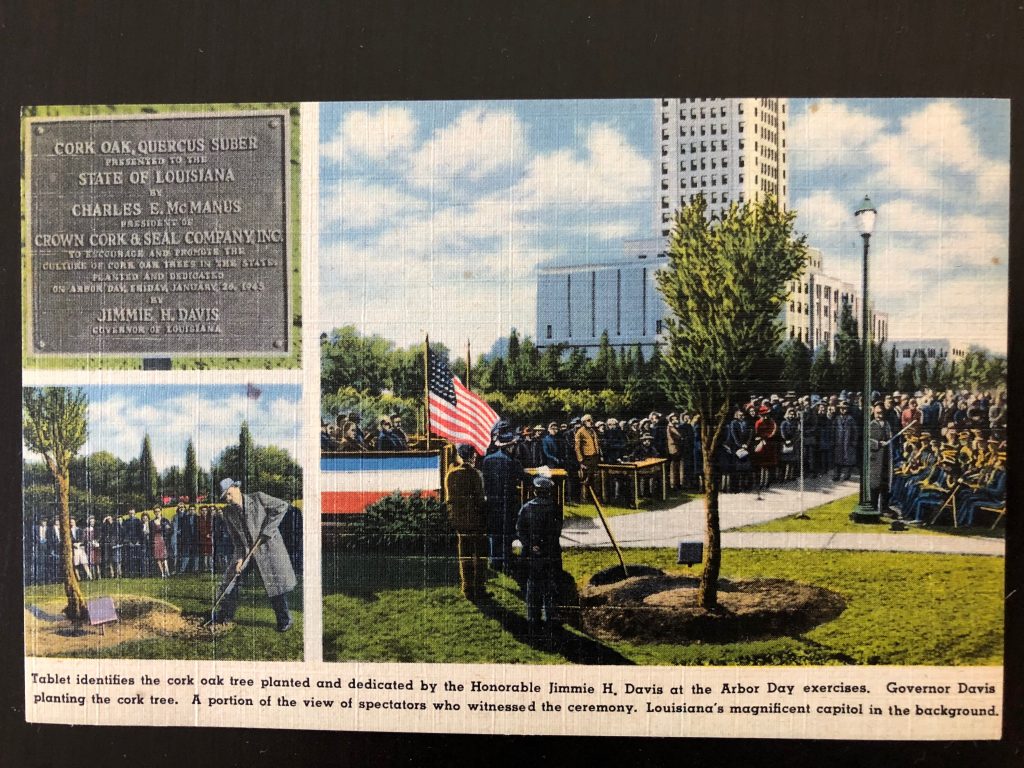

To promote Arbor Day events in various states, the company enlisted foresters and governors, along with marching bands and radio broadcast coverage. Hundreds of 4-H kids in each state lined up to plant seedlings. Planting trees gave them a way to channel wartime fears into action. They would be helping green the country, and maybe create a domestic supply for American businesses.

In January 1945, Woody Metcalf launched a cross-country tree-planting tour, leaving San Francisco in an 18-wheeler containing 12,000 California acorns. The Los Angeles Times printed an article about the tour and the campaign for making America self-sufficient on those trees. It said Metcalf "hoped that within 20 years sufficient cork may be produced to supply local needs."

In Arizona, Metcalf saw 10,000 seedlings growing at Superior, ready for distribution before Arbor Day in Arizona. Louisianans marked Arbor Day by planting cork oaks at the capitol grounds in Baton Rouge. There Governor Jimmie Davis, the songwriter behind the hit, “You Are My Sunshine,” hoisted a shovel for the occasion.

One boy in Maryland read about the cork project and sent off a request for acorns. By return mail came a box with three acorns packed in moss. He planted and watered them, and they sprouted. He kept watering them until they grew over 10 feet high. Seventy years later, he still remembers the trees’ dark green leaves.

Trees That Inspire

Survivors of that time are still found across the country today. They include trees in South Carolina where farm families joined in planting cork trees on Arbor Day far from Columbia, and trees in Arizona. Veterans from that campaign also grow on the California state capitol grounds and in the U.C. Davis arboretum, where Woody Metcalf managed the plantings. After writing a book about the World War II campaign, I visited the big trees in both locations.

They remind us that we have survived crises before, and they can encourage us to take up shovels to establish many more trees now. A planting campaign can cultivate young tree-planters and inspire us for a lifetime.

See what others are doing to celebrate Arbor Day. Visit celebratearborday.com

About the Author

David Taylor writes about revealing connections between people and their worlds. His writing about people, food, health and science has appeared in Smithsonian, The Washington Post, The Village Voice, Outside, The Christian Science Monitor, Science, and Oxford American.